| Home | About Us | Resources | Archive | Free Reports | Market Window |

|

Editor's note: Today's edition is a little unusual. While we normally feature essays in DailyWealth, today you'll find an interview with S&A Editor in Chief Brian Hunt. It covers one of the most valuable wealth-building concepts you'll ever read. It doesn't just apply to investments... it applies to just about any purchase you'll ever make. You'll want to make sure everyone in your family reads this one. Read on to learn...

The Most Important Aspect of Any InvestmentBy

Wednesday, June 4, 2014

If you want to be successful in stocks, there's one simple thing you have to do – focus on the price you pay. Buy at bargain prices.

It sounds simple. But most people can't bring themselves to do it.

Below, Stansberry & Associates Editor in Chief Brian Hunt explains this vital idea... and how you can use it to make winning investments.

Stansberry & Associates: Brian, at Stansberry & Associates, we urge people to focus on the price they pay for investments. Could you explain why this is so important?

Brian Hunt: Sure.

This whole idea comes down to treating your investments like you treat almost anything else you buy. The idea is that you should focus on finding good values... and not overpaying for things.

When you buy a pair of shoes, you want to pay a good price. When you buy a computer, you want to pay a good price. When you buy a house, you want to pay a good price. You don't want to overpay. You don't want to embarrass yourself by getting ripped off.

Yet... when people invest, the idea of paying a good price is often cast aside. They get excited about a story they read in a magazine... or how much their brother-in-law is making in a stock, and they just buy it. They don't pay any attention to the price they're paying... or the value they're getting for their investment dollar.

Warren Buffett often repeats a valuable quote from investment legend Ben Graham: "Price is what you pay, value is what you get."

I think that's a great way to put it.

S&A: How about an example of how this works?

Hunt: Like many investment concepts, it's helpful to think of it in terms of real estate...

Let's say there's a great house in your neighborhood. It's an attractive house with solid, modern construction and new appliances. It could bring in $30,000 per year in rent. This is the "gross" rental income... or the income you have before subtracting expenses.

If you could buy this house for just $120,000, it would be a good deal. Since $30,000 goes into $120,000 four times, you could get back your purchase price in gross rental income in just four years. In this example, we'd say you're paying "four times gross rental income."

Now... let's say you pay $600,000 for that house. Since $30,000 goes into $600,000 20 times, you would get back your purchase price in gross rental income in 20 years. In this example, we'd say you're paying "20 times gross rental income." Paying $600,000 is obviously not as good a deal as paying just $120,000.

Remember, in this example, we're talking about buying the same house. We're talking about the same amount of rental income.

In one case, you're paying a good price. You're getting a good deal. You'll recoup your investment in gross rental income in just four years.

In the other case, you're paying a lot more. You're not getting a good deal. It will take you 20 years just to recoup your investment. And it's all a factor of the price you pay.

S&A: Let's move on to a stock market example.

Hunt: Sure. It works the same way.

Let's say Company ABC generated $1 million in annual profit last year.

If you buy ABC at a market value of $6 million, you're paying six times earnings. If you buy ABC at a market value of $20 million, you're paying 20 times earnings. If you buy ABC for a market value of $50 million, you're paying 50 times earnings.

The market is made up of people. And people tend to act crazy from time to time. One month, the market might set the price of ABC at $6 million. The next month, it might set the price of ABC at $8 million or $10 million.

I know that sounds like a wide range of prices, but you see these ranges in the stock market all the time. People are willing to pay different prices for different businesses at different times.

The amount people are willing to pay for a company's earnings is often called the "price-to-earnings multiple," or simply "the multiple."

In this example, it's a much, much better deal to buy shares of ABC when the market is valuing it at $6 million – or at a price-to-earnings multiple of six – instead of buying shares when it is valued at $50 million – or a price-to-earnings multiple of 50. You get more value for your investment dollar. You're buying shares in a cash-producing enterprise for a lot less.

The job of the investor is to make sure to buy assets at reasonable prices... and avoid buying assets at bloated, expensive prices.

S&A: If you're buying a great business, does it really matter if you pay too much?

Hunt: It's vitally important to know that buying shares in a great business can turn out to be a terrible investment if you pay the wrong price.

Let's go back to ABC. Let's say it's a great company. It has a good brand and good profit margins. It's steadily growing. And remember, it does $1 million in annual profit.

If you purchase ABC shares at a market value of $100 million, that's paying 100 times earnings for ABC. This is an extremely expensive price. Your only shot at making money in this example is if someone else comes along and is willing to pay an even crazier price than you did.

While this "waiting for a greater fool" can work occasionally, it's generally a losing strategy. The regular investor will never be able to make it work.

What often happens is that the company keeps doing well, but the multiple people are willing to pay returns to more normal levels. In a case like this, the company can keep increasing its profits, but the share price will plummet. It can fall 50% or 75%.

I know this sounds extreme, but it's exactly what happened during and after the 1999 and 2000 market peak.

Back then, good companies with solid future prospects – like Wal-Mart and Microsoft – traded for 50, 60, even 90 times earnings. People who purchased shares back then paid stupid prices. They had speculative fever. They didn't focus on getting good value for their investment dollars.

Because many stocks with good business models were so overvalued, their share prices crashed and went nowhere for many years.

Keep in mind, the underlying businesses were still very sound. Those businesses were still growing. But the stock prices got so out of whack that investors who overpaid suffered horribly. It took a long time for the stocks to "work off" their extremely overvalued state.

For example, in 1999, Wal-Mart traded for more than 50 times earnings. It spent more than a decade working off that overvaluation. Folks who bought Wal-Mart back in 1999 didn't make any money for more than a decade. The company did fine... but shareholders who bought the stock at stupid prices suffered for a long time.

If you can buy a great business for 10 times earnings, it's a good deal. But if you pay 30 or 50 times earnings for it, you're bound to be disappointed.

I have to state it again: If you overpay, you can make a horrible investment in a great company.

S&A: One the other hand, you can make money in a poor business if you pay a bargain price, right?

Hunt: Yes. Let's look at another example...

Let's say Company XYZ is barely profitable with a market value of $2 million. It makes just $250,000 a year. And a competitor is doing a better job of serving customers... so sales are declining.

But let's also say that the company sits on a valuable piece of real estate, which it owns free and clear. You know the piece of property could easily sell for $3 million... maybe even $4 million.

You could buy up shares, knowing full well the business is in decline and could even stop being a profitable enterprise. But if you buy shares while the market values the company at $2 million, you could make a great profit if they close the business and sell the assets for at least $3 million.

In this example, you could make money in a bad business... by paying a bargain price. Again, it all comes down to the price you pay.

S&A: What if you're buying a stock to collect dividends? How do you know what a good price is?

Hunt: The price you pay for a dividend-producing stock is a huge deal.

Let's say Company ABC is a great business that pays a very stable dividend. It has raised its dividend every year for 29 consecutive years. Its current annual dividend is $1 per share.

If you bought ABC at $20 per share, your dividend yield would be 5%. If you bought ABC at $30 per share, your dividend yield would be 3.3%. If you bought ABC at $36 per share, your dividend yield would be 2.8%. If you bought ABC at $100 per share, your dividend yield would be just 1%.

As the price you pay goes up, the yield on your original investment goes down.

Obviously, you want to pay lower prices and earn higher yields.

It's a similar story with bonds. Bonds pay fixed-income payments. But like stocks, the price of bonds can fluctuate.

For example, let's say we have a bond that is issued at a price of $1,000. Let's say it pays a 5% interest rate. That's $50 in annual interest.

If investors lose faith in the company that issues the bond, the bond price could fall to $700. But the annual interest payment would remain $50.

In this case, the buyer of the bond who pays $700 would earn about 7% in annual interest. The difference in how much income you earn is all a function of the price you pay.

S&A: Any parting thoughts?

Hunt: The big takeaway here is that investors need to view their stock, bond, real estate, and commodity purchases just like they would view buying a house or a car or a phone or their groceries. Don't be a sucker and overpay. Make sure you get good value for your investment dollar. Hunt for bargains.

You wouldn't pay $50 for a gallon of milk, would you? So why would you pay absurd prices for stocks?

Before you buy an asset, study its valuation history. See what levels represent "good prices" and see what levels represent "stupid" prices. These prices vary from stock to stock and asset class to asset class. Make sure you buy at levels that represent historical bargains.

S&A: Great points. Thank you.

Hunt: You're welcome.

Summary: Investors need to view their stock, bond, real estate, and commodities purchases just like they would view buying a house, car, phone, or groceries – don't overpay. Even buying a great company at a "stupid" price can make for a terrible investment. Make sure you're getting a good value for your investment dollar by buying an asset at a good historical valuation.

Further Reading:

If you're looking for value in the market today, Steve Sjuggerud says you'll find it in European stocks. "European stocks would have to rise by more than 70% to equal the valuations of U.S. stocks today," he writes. "In short, despite Europe's long-term problems, European stocks could absolutely soar from here." Get all the details here.

"It's getting difficult to find new large-cap, high-quality names trading at cheap prices these days," Dan Ferris writes. "But there's still one World Dominator that looks like a screaming bargain right now... In fact, I think its share price should be about double where it is today." Learn more here.

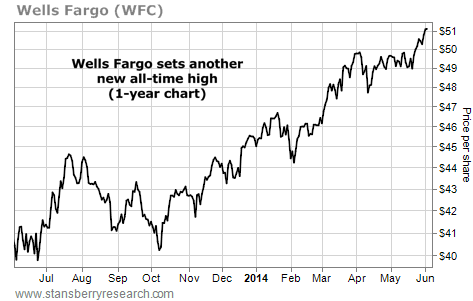

Market NotesA KEY AMERICAN STOCK CONTINUES TO SURGE AHEAD Wells Fargo just hit another new high. It's another sign things "can't be all that bad" in America.

Over the past three years, we've run dozens of charts that show while the American economy isn't humming, it can't be doing "all that bad." For example, we've highlighted the soaring share prices of transportation stocks, home-improvement stocks, and hotel stocks. Today, we look at shares of Wells Fargo.

With a market cap of around $200 billion, Wells Fargo is America's largest bank. It's also the nation's largest issuer of mortgages. It's a favorite holding of superinvestor Warren Buffett.

Like almost every financial company, Wells Fargo was hammered in the 2008/2009 credit crisis. But since bottoming in 2009, it has been all recovery for Wells Fargo. It has "digested" the bad debts of years past, and it's now increasing earnings. Things are going so well that the stock just reached another new all-time high. Things can't be all that bad in America!

|

Recent Articles

|